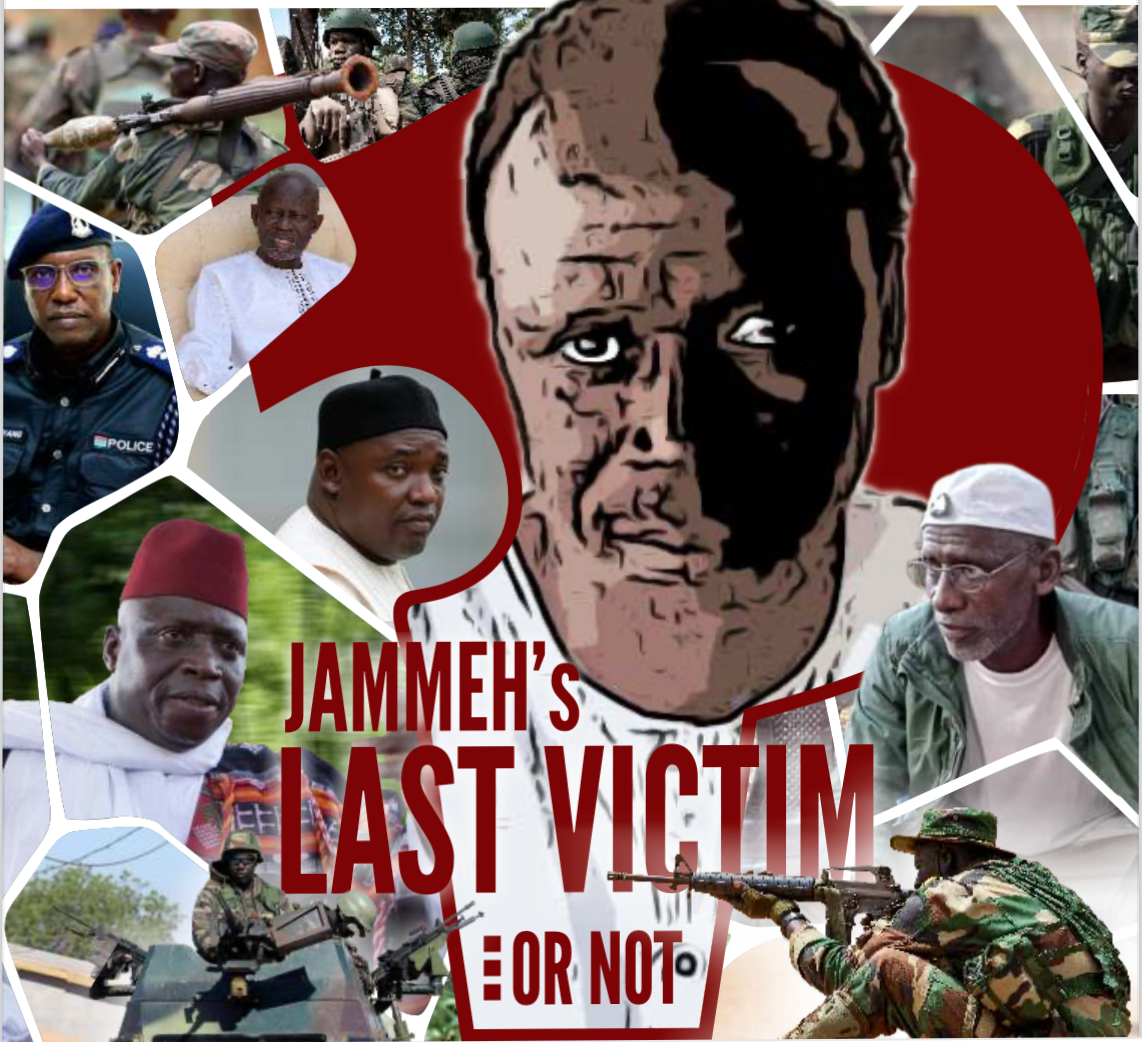

JAMMEH’s LAST VICTIM - OR NOT

By Mariam Sankanu

Thursday, 27 February 2017. Darkness creeps in, and Siaka Fatajo has not returned home. It has been hours since he left for a memorial service in Karunorr village on the border with the conflict-ridden Casamance region of Senegal. He hasn’t telephoned. Nor has he been answering calls.

For his wife, Jainaba Saidy, this was not just unusual. Something wasn’t right about it. After all, her family has been living on the edge in the village in recent times. Her daughter, Mariama, was a subject of complaint at the police after a brawl fight with a mate at the village tap. A week later, her husband had a complaint filed against him at the police. Barely 24 hours after that, the village chief convened what turned out to be a tense meeting over the same allegation that Siaka, who identifies as a Mandinka, had insulted the Jolas.

“When he came from that meeting, he called for a family meeting and told us from now on, be very careful of what you say or what you do,” Jainaba, 49, recalled.

Siaka’s first wife, Jainaba Fatajo, sitting in her room. Mariam Sankanu/Malagen

Siaka’s first wife, Jainaba Fatajo, sitting in her room. Mariam Sankanu/Malagen

“So, I got worried when I could not get him on the phone,” she added.

But she wasn’t alone. Her husband’s friend, Saikabou Conteh, had been trying to reach Siaka on the phone. News was spreading about an alleged conspiracy to harm him. He was to be advised not to go near the border. The race to stop him turned frantic. Too little, too late.

Six years on, Jainaba and her children have been living with the ambiguity of not knowing whether their loved one is alive or dead.

“If I look at him, I cry,” she said, referring to her son, Zakir, now six years of age. At this point, her eyes welled up. She took a pause, before picking the edge of her veil to wipe her tears.

She narrated how she is isolated in the village. Her job as a nurse at the village dispensary was taken from her. Her letters to the presidency never got a response. Her calls to people believed to be in the know about Siaka’s whereabouts get ignored. Some of the sources blocked her phone numbers. Her husband is not even remembered - his face is missing on his party, UDP’s album of martyrs.

“Siaka was the breadwinner, but now I have taken on that responsibility,” she managed to say in between sobs. “When he disappeared, the whole village abandoned me. They have never asked me about him.”

“The people here hate seeing me come to this house,” said Bakary Sangyang, Siaka’s closest friend in the village. “But they would not dare say it.”

Yet, in a curious irony, Bakary used the ‘backdoor’ to meet this reporter at Jainaba's house. "I had to avoid some eyes seeing me coming here," he said.

How did it come to this for Jainaba and her family?

The enemy within

Rewind. December 2, 2016. Yahya Jammeh had lost at the polls to an opposition coalition. The atmosphere was filled with joy. Wild celebrations took off across the country.

But in Jammeh’s native Foni region, the fall of the son of the land known to them as the ‘Big Man’ is no victory. Siaka Fatajo lives in the heart of the region. His village, Batabutu Kantaro, is in Foni Bintang district where Jammeh had just won 84 percent of the votes, the highest in the country, after Jammeh’s native Kansala.

As soon as Barrow was declared winner, Siaka hopped on his motorbike and rode to the outskirts of the village to pick his friend Bakary Sangyang, though the two belonged to opposing parties.

“I sat at the back and held a UDP flag after he picked me,” said Sanyang who was a then ruling APRC supporter and had voted for Jammeh.

Bakary said Siaka used to visit him almost everyday. It is one of such visits when Siaka’s troubles started to escalate.

“I went inside [the bedroom] and left him on my veranda talking on the phone to our friend,” he explained. “When I came back, I heard Yama [my granddaughter] quarrelling. She said she heard Siaka insulting Jolas.”

Sanyang received a phone call the following morning from the police station in Sibanorr. Yusupha Sanyang, his nephew, had filed a complaint against Siaka over Yama’s allegations. Siaka named him as his witness.

“I told the police that the allegation against Siaka was a lie. I'd just gone into my room and Siaka was on the veranda. Yama was standing 6 to 7 metres away. So how could she hear that and I could not. And Siaka won’t dare come to my house, and insult my family and tribe.”

Matters did not end there. The following day, the village chief, Almami Sangyang convened a meeting over the same issue.

“The purpose of the meeting was to call for unity,” the village chief told Malagen, denying that it was over the Siaka-Yama issue.

However, at least three witnesses explained that when the meeting started, the village chief announced the complaint filed against Siaka with respect to his election victory celebrations and putting up a UDP flag at his gate.

“I went with Siaka to the meeting, and the turnout was unusually high,” said Bakary.

“They are of the view that you have taken yourself to not be one of us. Because there are some villagers working in Yahya Jammeh’s government. And now that Yahya Jammeh is out, they will all be removed,” he recalled the alkalo telling Siaka.

He said even though Siaka had apologised, promised to bring down the flag and clarified that his celebration was not meant to make mockery of people who would lose their jobs, insults and derogatory comments continued. Speaker after speaker expressed anger over Siaka’s victory celebration, Sanyang said.

“Then, he [Siaka] told the alkalo I believe you called this meeting because of me. Everyone saying they want to speak, they do not want to say anything if not about me. So if this does not end in peace by God’s grace and I become a corpse, then you killed me. Because you called for this meeting.”

Visibly emotional, Bakary squeezed the inner corners of his bloodshot eyes with his thumb and forefinger. As he continued to speak, voice kept breaking. He took a deep breath, sucking his teeth and shaking his head.

“All the accusations against him, that is not his character,” he said, referring to his missing friend.

Siaka, the spy

Senegal’s southern region of Casamance has been trapped in conflict since the 1980s. Some of the areas controlled by the Salif Sadio led MFDC forces share borders with the Foni region in The Gambia. This makes it easy for the rebels, in guerilla style, to cross into in the country to get shelter, according to our sources, backed by official accounts.

“The rebels normally come here. They have relatives all over. So, we are interrelated,” said Omar Sanneh (not his real name), a youth activist and resident of one of the villages neighbouring Batabutu.

“Let me make it clear to you. The rebels are not in the bushes. Some of the people registered here as refugees are the same people who pick up guns and go to Casamance to fight,” a Foni-based ruling NPP supporter, who does not want to be named, also told Malagen.

Former President Yahya Jammeh has long been accused of backing the rebellion. So, when he was removed from power in January 2017, the Ecowas military intervention in The Gambia (ECOMIG) set up bases and checkpoints in various parts of Foni. The mandate of ECOMIG is to ‘restore democracy’, but the contingents dominated by Senegalese military have been using Gambia as a launchpad to squeeze life out of Africa’s longest running guerilla movement.

Clashes between the rebels and Senegalese forces have since escalated. Foni is no longer a safe-haven, it has become a frontline. The people are not just caught up in the conflict. They claim that they are being targeted by the Senegalese military. At least five Gambians have since been killed and over 18,000 displaced due to recent clashes last year.

But it is not only the Senegalese forces that have been reportedly committing human rights violations in Foni. The rebels seem to have a curious dominance in the region. Residents told Malagen the rebels have long been used as a tool to threaten and abuse political opponents.

“You know the rebels are strong supporters of the APRC,” Omar’s brother, who also prefers to be anonymous ‘due to my safety’, told Malagen.

“All of us, our names were booked and given to rebels,” said Assan Jobarteh, Siaka’s friend, and chairman of the ruling NPP in Foni Bintang district.

“If we had not won [in 2016], you would not have met me here today. By now, we would all have disappeared,” he added.

When Siaka disappeared, accusing fingers were pointed at former President Yahya Jammeh. The trader became known to transitional justice activists and investigators of human rights violations as the last victim of Jammeh. Widely labelled as a dictator, Jammeh presided over a regime characterised by human rights violations. Unlawful killings, enforced disappearance and torture were commonplace.

But those familiar with Siaka’s case said that Jammeh, who was already in exile in Equatorial Guinea, did not have any direct hand in the disappearance. More than dozen sources, including former rebels, rebel insiders and police sources have disclosed to Malagen that Siaka was kidnapped by elements of the MFDC.

But it was not without the conspiracy of the villagers aggrieved by Siaka’s political activities following the defeat of Jammeh.

“The betrayal was cooked here,” said Bakary, Siaka’s friend. “The rebels were told that Siaka was a spy for ECOMIG.”

Siaka the spy. An easy story to sell to the rebels, isn’t it? The ECOMIG military base in the village is barely three minutes walk from Siaka’s home and he frequents there. But he is also a petty trader, who travels on his bike, selling a variety of goods in various villages in Foni and Casamance. He is a regular supplier of medicines to the rebels.

Dead or alive

Omar Sanneh, known as Baitullah (meaning house of God), is an ex-soldier turned controversial conspiracy theorist, who has become popular especially in Foni for his revealing, oftentimes invective and anti-government WhatsApp audios he broadcasts from unknown locations.

In one of his audios published in 2019, attacking the ruling NPP, he threatened that they’d suffer the fate that Siaka had met.

“That UDP member in Batabut used to sneak into Casamance. He used to say there are rebels in Foni. He went to Casamance. Something Fatajo. He would not repeat it again. He will narrate the story in the hereafter…,” he said.

For Saikou Fatajo, Siaka's younger brother, this revelation has dashed their hopes.

“When I heard Baitulai mention Siaka in the manner he did, that was the moment I became more worried because I think Baitullah knows something that we didn't know,” he said.

More than dozen sources, including former rebels, rebel insiders and police sources have disclosed to Malagen that Siaka was captured in Foni, on Gambian soil, and taken into Casamance where he was beaten to death by elements of the MFDC.

“Siaka was not taken to the camp. He was killed on the same day he was captured,” a rebel insider told Malagen.

The alleged rebels who are believed to have kidnapped and killed Siaka are not all based in Casamance, our sources said. Some of them, named and located by our sources, are living in various villages in Foni. One of them lives in Batabut, our sources said.

“I used to investigate this matter,” Siaka's friend, Ansumana Fabureh also told Malagen. “The clothes he was killed in are with someone. The person is in Foni around the borders. He wanted to bring the clothes, but he was scared. So someone suggested that he put it in a plastic bag at night and throw it in the house, but he refused.”

For ethical and legal reasons, Malagen could not publish the identities of the people alleged to be rebels behind Siaka’s disappearance and killing.

When duty bearers fail victims

Upon assuming office in 2017, the Gambia government under President Adama Barrow has signed up to a good deal of international human rights instruments.

“The priority of the government is to put in place a new and resilient architecture to uphold the highest standards when it comes to human rights, justice and rule of law,” said then Justice Minister, Abubacarr Tambadou.

One of the instruments the country was quick to put its name to is the UN Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (CRED), signed on 20 Sept. 2017 and ratified on 28 Sept. 2018. Among many protective measures, it accords families the legal right to know the fate of their loved ones.

Human rights lawyer Gaye Sowe said the government has an obligation under international law to carry out an effective investigation into the disappearance of Siaka Fatajo.

“The issue is, governments must investigate human rights violations irrespective of who the perpetrator is, whether a public official or a private actor,” Gaye Sowe, citing a host of other international human rights instruments - and Gambian law.

“The investigations must meet the due diligence standard, and would entail investigating, identifying the perpetrator, prosecuting and punishing the perpetrator and providing the victim with a remedy,” he said.

In Siaka’s case, the government’s efforts, if there were any, did not appear to match its legal duty.

Malagen investigation gathered that when Siaka’s disappearance was reported, the police and district authorities formed a ‘task force’ comprising some village chiefs, Seyfo’s assistant and some security officials.

The investigations lasted only a few hours.

“They gave us a vehicle. There were a lot of us. We went to Karunorr where his family said he went, and asked but they said they did not see him. Afterwards, nobody heard about it again. The issue was silent,” the village chief said.

As for the police station in Sibanorr, the officer-in-charge was redeployed shortly after the incident. The officer leading the investigation followed shortly afterwards.

“But he [the investigator] wrote a Note to the Command upon the conclusion of investigations,” our source said. The Note, it turns out, was just a short message to indicate that Siaka was not found.

Malagen could not lay hands on any official reports on Siaka’s case. There seems to be none.

But Siaka’s family and relatives had not called off the search, reporting the case to various state security agencies, including Interpol, Serious Crimes and the police high command.

“So the government that should investigate this has taken no action,” said one of Siaka’s friends. “There is no police officer who could tell you they have investigated Siaka’s issue properly.”

Malagen has confirmed that the case has been filed before the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) who had written to the state authorities, asking them to properly investigate the case and provide remedy for the family.

Mansour Jobe, the director of legal and investigation, NHRC said when his office received the complaint in Sept. 2020, they quickly reached out to relevant authorities over the matter.

“Unfortunately, since then, we did not receive a response from the office of the Inspector General of Police to our letter dated 15th September 2020,” he told Malagen.

“The Minister of Interior acknowledged receipt of our letter and also urged the police to provide us with the relevant information on this case. Since then, we have been making some follow-ups with the police for updates, but we have not received a formal update from the police yet,” he added

Siaka wife, Jainaba, said they have written at least two letters to President Adama Barrow as well as the Attorney General, for them to weigh in and investigate Siaka’s disappearance. The family has not received any response yet from either the presidency or the attorney general.

Malagen has reached out to the ministry, but the officials there could not locate the letters. The Office of the President has failed to respond to our questions.

Malagen had a brief meeting with the police PRO, Binta Njie, at her office regarding the issue. We requested an official update on the case, and she asked that we write to her office. We wrote to the police and made subsequent follow-ups. According to receptionists at the station, the letter was handed to the registry’s office. Officials at the registry’s office however claimed to not have received any letter from Malagen.

As for the UDP, the spokesperson, Alamami Taal, indicated that he had little knowledge about the case.

“Surely, this is a police matter and I don’t know if characterising it as a partisan matter is helpful. Clearly, you have more information about this matter than I do,” he said.

“My point is, enforced disappearance is a very serious matter and is against domestic and international laws, so the focus must be on that and not party affiliation.”

The pain of living with absence

Unable to know Siaka’s fate or trace his whereabouts, the family and relatives have been left in limbo, six years and counting, without finding the closure of mourning.

His second wife has remarried, but for Jainaba, the search and wait continues as she nurses a shrinking hope that her husband is alive and will come home to her.

Mariama Fatajo, Siaka's daughter, is now a human rights and transitional justice activist. She works for the Women's Association for Victims' Empowerment (WAVE), a pro-women human rights organisation. @Malagen

Mariama Fatajo, Siaka's daughter, is now a human rights and transitional justice activist. She works for the Women's Association for Victims' Empowerment (WAVE), a pro-women human rights organisation. @Malagen

“I can feel what my mom is going through. She still believes that my dad will show up one day,” said Mariama.

The 26-year-old does not share her mother’s hope, but her younger brother, Zakariya, is as well clinging on to the belief that his father is not dead.

“My dad will come back one day,” Zakariya, in his 20s, told Malagen. “I dream about him sometimes. He is a strong man and the rebels will not be able to take him down like that.”

The grief at the absence is worsened by social and financial difficulties the family is going through. There has been no form of economic, psychosocial or psychological support.

“No one in the village got up to fight for me,” Jainaba said. “They knew my husband was responsible for us and he’s not there. Now I have to provide for the family.”

The only person she turns to for help is Saikou Fatajo, a brother to her husband.

“Even if one's sheep or goat goes missing in this village, people ask about it,” Saikou told Malagen. “But no one is asking us about Siaka. No one is bothered. So what do they know that we do not know?”

Saikou Fatajo is Siaka's younger brother. He was speaking about the case of his brother at the launch of the maiden print edition of Malagen. @Malagen.

Saikou Fatajo is Siaka's younger brother. He was speaking about the case of his brother at the launch of the maiden print edition of Malagen. @Malagen.

After Jainaba’s job at the village dispensary was taken from her, or allegedly, she now turns to selling vegetables at the village.

Siaka has 11 children, 9 of them with Jainaba. She said children have been hit hard, especially her last born, Zakir, who grew up not knowing his father. He refers to his sister, Mariama’s husband, as his father.

In 2019 - two years after Siaka’s disappearance - Ousman, the second son, embarked on the journey to Europe using the ‘back way’.

“I cried my eyes out every day, begging him to return,” Jainaba said. “I told him your father left and never came back. Now you also want to leave me. Do you want to kill me? Even if we eat sand every day, please come back.”

Story by Mariam Sankanu

Editor’s note: Some of the names in this story have been changed to protect the identity of sources that provided us with information.